Format of Program and Variables in Memory

Annex D to BBC BASIC (Z80)

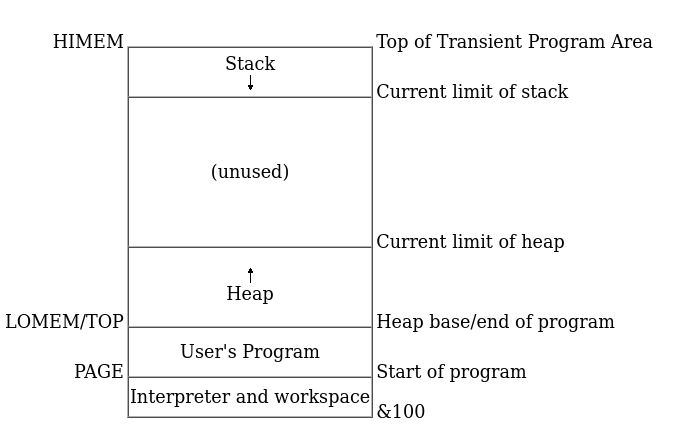

Memory Map

BBC BASIC (Z80) runs under the CP/M-80 operating system. It requires about 15 Kbytes of code space. The interpreter’s internal variables occupy approximately 1 Kbyte of memory

By default, your program will start on the page boundary immediately following the interpreter’s data area and the 'dynamic data structures' will immediately follow your program. The total group of the dynamic data structures is called the 'heap'. The base of the program control stack is located at HIMEM.

As your program runs, the heap expands upwards towards the stack and the stack expands downwards towards the heap. If the two should meet, you get a 'No room' error. Fortunately, there is a limit to the amount by which the stack and the heap expand.

In general, the heap only expands whilst new variables are being declared. However, bad management of string variables can also cause the heap to expand.

In addition to running your program, the stack is also used 'internally' by the BBC BASIC (Z80) interpreter. Its size fluctuates but, in general, it expands every time you increase the depth of nesting of your program structure and every time you increase the number of local variables in use.

The Memory Map

The function of HIMEM, LOMEM, TOP and PAGE are briefly discussed below. You will find more complete definitions elsewhere in this manual. You can directly set HIMEM, LOMEM and PAGE. However, for most of your programs you won’t need to alter any of them. You will probably only need to change HIMEM if you want to put some machine code sub-routines at the top of memory.

The first address at the top of memory which is not available for use by BBC BASIC (Z80). The base of the program stack is set at HIMEM. (The first 'thing' stored on the stack goes at HIMEM-1.) |

|

The start address for the heap. The first of the dynamic data structures starts at LOMEM. |

|

The first free location after the end of your program. Unless you have set LOMEM yourself, LOMEM=TOP. You cannot directly set TOP. It alters as you enter your program. The current length of your program is given by: |

|

The address of the start of your program. You can place several programs in memory and switch between them by using PAGE. Don’t forget to control LOMEM as well. If you don’t, the heap for one program might overwrite another program. |

Memory Management

There is little you can do to control the growth of the stack. However, with care, you can control the growth of the heap. You can do this by limiting the number of variables you use and by good string variable management.

Limiting the Number of Variables

Each new variable occupies room on the heap. Restricting the length of the names of variables and limiting the number of variables used will limit the size of the heap. However, of the techniques available to you, this is the least rewarding. In addition, it leads to incomprehensible programs because your variable names become meaningless. You should keep this technique in the back of your mind whilst you are programming, but only apply it rigorously if you are really stuck for space.

String Management

Garbage Generation

Unlike numeric variables, string variables do not have a fixed length. When you create a string variable it is added to the heap and sufficient memory is allocated for the initial value of the string. If you subsequently assign a longer string to the variable there will be insufficient room for it in its original position and the string will have to be relocated with its new value at the top of the heap. The initial area will then become 'dead' and the heap will have grown by the new length of the string. The areas of 'dead' memory are called garbage. As more and more re-assignments take place, the heap grows and eventually there is no more room. Thus, it is possible to run out of room for variables even though there should be enough space.

Memory Allocation for String Variables

You can overcome the problem of 'garbage' by reserving enough memory for the longest string you will ever put into a variable before you use it. You do this simply by assigning a string of spaces to the variable. If your program needs to find an empty string the first time it is used, you can subsequently assign a null string to it. The same technique can be used for string arrays. The example below sets up a single dimensional string array with room for 20 characters in each entry, and then empties it.

10 DIM names$(10)

20 FOR i=0 TO 10

30 name$(i)=STRING$(20," ")

40 NEXT

50 stop$=""

60 FOR i=0 TO 10

70 name$(i)=""

80 NEXTAssigning a null string to stop$ prevents the space for the last entry in the array being recovered when it is emptied.

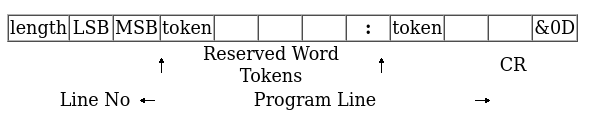

Program Storage in Memory

The program is stored in memory in the format shown below. The first program line commences at PAGE.

Line Length

The line length includes the line length byte. The address of the start of the next line is found by adding the line length to the address of the start of the current line. The end of the program is indicated by a line length of zero and a line number of &FFFF.

Line Number

The line number is stored in two bytes, LSB first. The end of the program is indicated by a line number of &FFFF and a line length of zero.

Statements

With the exception of the symbols '*', '=' and '[' and the optional reserved word LET, each statement in the line commences with the appropriate reserved word token. Reserved words are tokenised wherever they occur. A token is indicated by bit 7 of the byte being set. Statements within a line are separated by colons.

Variable Storage in Memory

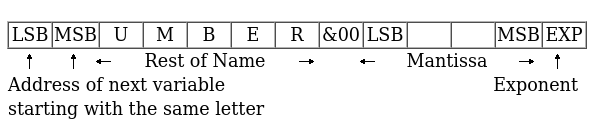

Variables are held within memory as linked lists (chains). The first variable in each chain is accessed via an index which is maintained by BBC BASIC (Z80). There is an entry in the index for each of the characters permitted as the first letter of a variable name. Each entry in the index has a word (two bytes) address field which points to the first variable in the linked list with a name starting with its associated character. If there are no variables with this character as the first character in the name, the pointer word is zero. The first word of all variables holds the address of the next variable in the chain. The address word of the last variable in the chain is zero. All addresses are held in the standard Z80 format - LSB first.

The first variable created for each starting character is accessed via the index and subsequently created variables are accessed via the index and the chain. Consequently, there is some speed advantage to be gained by arranging for all your variables to start with a different character. Unfortunately, this can lead to some pretty unreadable names and programs.

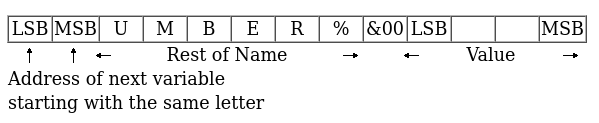

Integer Variables

Integers are held in two’s complement format. They occupy 4 bytes, with the LSB first. Bit 7 of the MSB is the sign bit. To make up the complete variable, the address word, the name and a separator (zero) byte are added to the number. The format of the memory occupied by an integer variable called 'NUMBER%' is shown below. Note that since the first character of the name is found via the index, it is not stored with the variable.

The smallest amount of space is taken up by a variable with a single letter name. The static integer variables, which are not included in the variable chains, use the names A% to Z%. Thus, the only single character names available for dynamic integer variables are a% to z% plus _% and `% (CHR$(96)). As shown below, integer variables with these names will occupy 8 bytes.

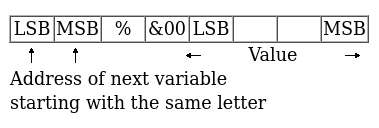

Real Variables

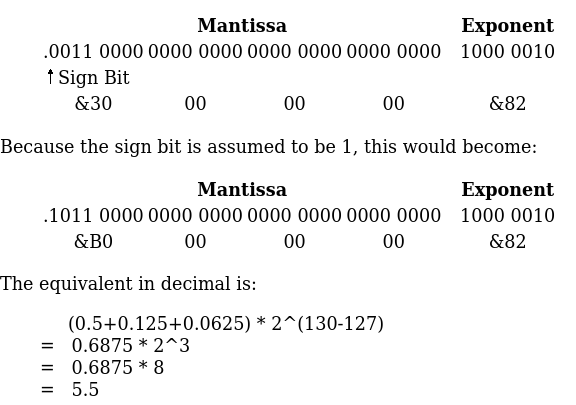

Real numbers are held in binary floating point format. The mantissa is held as a 4 byte binary fraction in sign and magnitude format. Bit 7 of the MSB of the mantissa is the sign bit. When working out the value of the mantissa, this bit is assumed to be 1 (a decimal value of 0.5). The exponent is held as a single byte in 'excess 127' format. In other words, if the actual exponent is zero, the value of stored in the exponent byte is 127. To make up the complete variable, the address word, the name and a separator (zero) byte are added to the number. The format of the memory occupied by a real variable called 'NUMBER' is shown below.

As with integer variables, variables with single character names occupy the least memory. (However, the names A to Z are available for dynamic real variables.) Whilst a real variable requires an extra byte to store the number, the '%' character is not needed in the name. Thus, integer and real variables with the same name occupy the same amount of memory. However, this does not hold for arrays, since the name is only stored once.

In the following examples, the bytes are shown in the more human-readable manner with the MSB on the left.

The value 5.5 would be stored as shown below.

BBC BASIC (Z80) stores integer values in real variables in a special way which allows the faster integer arithmetic routines to be used if appropriate. The presence of an integer value in a real variable is indicated by the stored exponent being zero. Thus, if the stored exponent is zero, the real variable is being used to hold an integer and the 4 byte mantissa holds the number in normal integer format.

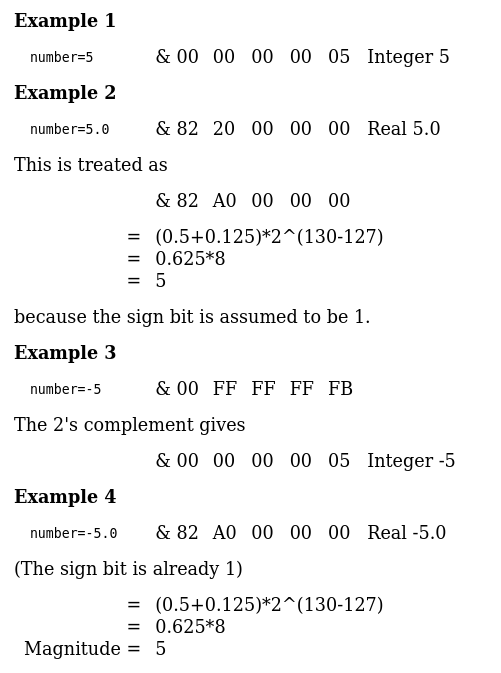

Depending on how it is put there, an integer value can be stored in a real variable in one of two ways. For example,

number=5will set the exponent to zero and store the integer &00 00 00 05 in the mantissa. On the other hand,

number=5.0will set the exponent to &82 and the mantissa to &20 00 00 00.

The two ways of storing an integer value are illustrated in the following four examples.

If all this seems a little complicated, try using the program on the next page to accept a number from the keyboard and display the way it is stored in memory. The program displays the 4 bytes of the mantissa in 'human readable order' followed by the exponent byte. Look at what happens when you input first 5 and then 5.0 and you will see how this corresponds to the explanation given above. Then try -5 and -5.0 and then some other numbers. (The program is an example of the use of the byte indirection operator. See the Indirection section for details.)

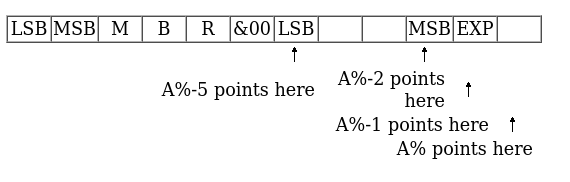

The layout of the variable 'NMBR' in memory is shown below.

10 NUMBER=0

20 DIM A% -1

30 REPEAT

40 INPUT"NUMBER PLEASE "NUMBER

50 PRINT "& ";

60 :

70 REM Step through mantissa from MSB to LSB

80 FOR I%=2 TO 5

90 REM Look at value at address A%-I%

100 NUM$=STR$~(A%?-I%)

110 IF LEN(NUM$)=1 NUM$="0"+NUM$

120 PRINT NUM$;" ";

130 NEXT

140 :

150 REM Look at exponent at address A%-1

160 N%=A%?-1

170 NUM$=STR$~(N%)

180 IF LEN(NUM$)=1 NUM$="0"+NUM$

190 PRINT " & "+NUM$''

200 UNTIL NUMBER=0String Variables

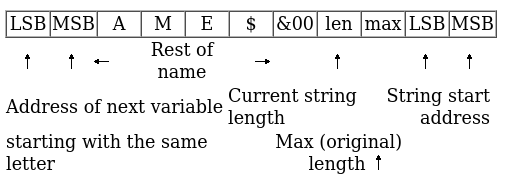

String variables are stored as the string of characters. Since the current length of the string is stored in memory an explicit terminator for the string in unnecessary. As with numeric variables, the first word of the complete variable is the address of the next variable starting with the same character. However, since BBC BASIC (Z80) needs information about the length of the string and the address in memory where the it starts, the overheads for a string are more than for a numeric. The format of a string variable called 'NAME$' is shown below.

When a string variable is first created in memory, the characters of the string follow immediately after the two bytes containing the start address of the string and the current and maximum lengths are the same. While the current length of the string does not exceed its length when created, the characters of the string will follow the address bytes. When the string variable is set to a string which is longer than its original length, there will be insufficient room in the original position for the characters of the string. When this happens, the string will be placed on the top of the heap and the new start address will be loaded into the two address bytes. The original string space will remain, but it will be unusable. This unusable string space is called 'garbage'. See the Variables sub-section for ways to avoid creating garbage.

Because the original length and the current length of the string are each stored in a single byte in memory, the maximum length of a string held in a string variable is 255 characters.

Fixed Strings

You can place a string starting at a given location in memory using the indirection operator '$'. For example,

$&8000="This is a string"would place &54 (T) at address &8000, &68 (h) at address &8001, etc. Because the string is placed at a predetermined location in memory it is called a 'fixed' string. Fixed strings are not included in the variable chains and they do not have the overheads associated with a string variable. However, since the length of the string is not stored, an explicit terminator (&0D) is used. Consequently, in the above example, byte &8010 would be set to &0D.